Today’s blog is written by guest blogger Rebekah Zemansky. Reposted from The ISHI Report with permission.

“We’ve been told that current crossings are down, so deaths are going to be down,” Dr. Bruce Anderson says. “We’ve not been under a hundred and forty deaths in a calendar year in a decade.”

Anderson has been a forensic anthropologist at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner in Tucson, Arizona for over 20 years. We’re meeting in PCOME’s library for an update about the caseload of unidentified bodies that fit the profile of migrants, people crossing the US-Mexico international border between Arizona and Sonora.

Positioned on major transit routes for goods and people, popular for tourists from around the world, Arizona always had a highly mobile population of people moving through the state from around the world.

Southern Arizona became a preferred place to cross in the 1990s, when U.S. immigration officials implemented tougher border enforcement through Operation Gatekeeper in California and Operation Hold the Line in Texas. The clampdown in those states funneled more illegal immigrant traffic into Arizona. In the meantime, border security increased across the board, with more formidable fences and an increase in Border Patrol officers. All this has resulted in smugglers leading migrants through more remote territory — higher into the mountains, farther from towns and highways and deeper into the desert.

There’s no way to know how many people cross. What’s available is arrest data from Customs and Border Patrol, which may include the same people attempting to cross the border and getting caught multiple times, and the number of dead who are recovered by hikers, hunters and humanitarian volunteers who report the bodies to law enforcement.

According to the Department of Justice’s NamUs database which has tracked longer term missing persons and unidentified cases since 2009, Arizona is usually in the top 4 states for unidentified bodies nationwide. Missing persons cases statistics are not far behind (the other states with consistently high counts in both categories: New York, California, Texas and Florida).

Sometimes things fall into place — a missing person’s report matches a physical description of a body or details provided by relatives searching for loved ones. But even in the successful cases, the process of identifying the dead is a painstaking one.

“Border Patrol has so many agents in the field that I know they are doing a better job today than they were fifteen years ago as far as coverage.”

“The wider coverage is helping with recoveries?” I ask.

“Extra agents help with recoveries of both current and old deaths,” He agrees. “But the PMI, the Post-Mortem Interval has gone up and with that our chances for a traditional easy ID went down so they become virtually all DNA based.”

Between 2001 and 2010, the Pima County office of the Medical Examiner handled more than 1,500 border crosser deaths. The series seemed to start overnight in 2001 when a single case delivered 14 bodies to their doors, the beginning of a flow that showed no signs of easing. More than 500 were John or Jane Does — people whose bodies have been too damaged by the harsh desert conditions or who carry no verifiable identification.

Dr. Bruce Parks was the Medical Examiner for Pima County from 1991 to 2011.

“It’s been going on now for over ten years and there are offices like this which are involved in finding out who the people are and there are offices doing other aspects of the work to try to locate these people and save them and take care of them and render medical care, if they’re lucky enough to survive,” Parks said in 2010. “So in southern Arizona, and a few other places along the border, it’s a big deal and it’s a sad situation.”

This spike has driven some unique forensic and policy problem solving at organization, county and now state levels. Forensically there’s new techniques for fingerprinting and skeletal measurements. There’s new law enforcement coordination policies like the Missing in Arizona program (MiA) program and new outreach efforts to locate family members throughout the United States who may both need answers and have information to benefit the case.

These techniques developed in Arizona are also actively being exported to other jurisdictions. (Examples include the Tucson based Colibri NGO helping Texas NGO’s mediate between family and law enforcement to identify migrant bodies recovered from graves in Brooks County as well as Arizona forensic anthropologists exchanging information with colleagues in Germany handling identification work for migrants who died after being locked in a truck or people washing ashore in Italy after their boats go down in the Mediterranean).

Pima County identifies about 70 percent of the bodies brought in. Yet staff members push themselves to do better — they know that for the 30 percent of their cases that are unresolved they cannot return the body to family members. And those mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, husbands and wives may never be at peace.

Law enforcement and case managers for DOJ’s NamUs program call the situation of missing persons and unidentified bodies in the United States “the nation’s silent mass disaster.”

Performing DNA analysis on skeletal samples that have been degraded by the harsh desert conditions requires specific techniques. This also puts additional strain on local government labs dealing with high caseloads. In this instance, Pima County has outsourced samples to BODE Technology, a private lab based in Virginia specializing in DNA recovery.

Anderson explains that BODE Technology has over 900 profiles from PCOME unidentified cases who are presumed to be border crossers.

“DNA exams take a minimum of two or three months,” Dr. Bruce Anderson says. “We have a backlog of cases that we have not got to yet and we also have a backlog of cases where we know who they are but we just haven’t proven it with DNA yet – and those bodies stay here.”

And then he drops a surprise.

“If you want to come back to the lab I can show you a case,” Anderson says. “A presumed migrant, with all the trappings, clothing wise of the migrant, the right age, found out in a remote part of the desert. We are clueless as to who it is. And I’ll cut a bone sample and pull a tooth and package those up.”

The anthropology lab is roughly twenty feet by ten feet, walls lined with counters and shelves and with the doors into other hallways on each end. With multiple people and two full sized autopsy tables out, space is tight.

The bones are already laid out and arranged precisely on a wheeled metal table under a white cloth. Measurement markings running down the narrow, slightly higher sides.

The tools are also laid out on a white towel over a black counter next to the sink: scissors, pliers, picks. A container of bleach sits in the sink.

As he puts on gloves and a ventilation mask, Anderson discusses the skeleton, a case he’s been looking at for about a week.

Photo Credit: Rebekah Zemansky

“These arm bones were laying in the sun for maybe six months to a year,” Anderson says. “He was found in May, so could be Christmas or maybe even last summer for his death.”

The general stats for the border crossing cases for the last decade: eighty percent are men, sixty-five to seventy percent are between twenty and thirty-five. Most men are around five foot seven, women usually three to four inches shorter.

“He is average height, he is 5.6 feet,” Anderson says. “He’s between thirty years and forty years, maybe a little bit younger. He is so typical of most male migrants that that’s not going to be distinguishing. But we are hoping that one of those two items, either the backpack or the shirt, might be.”

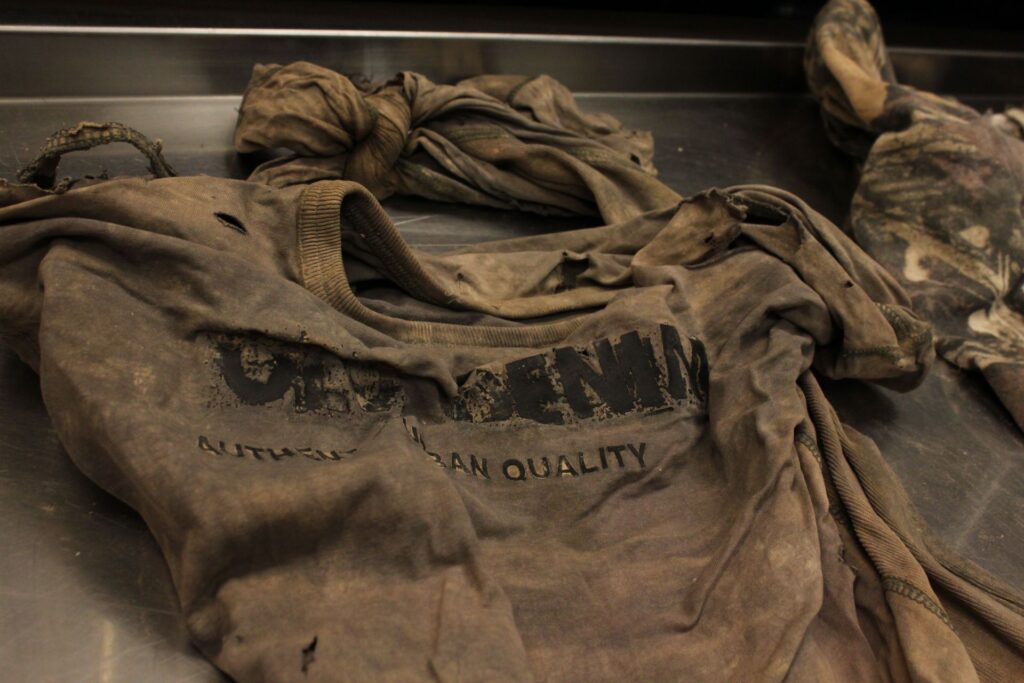

He shows the clothing brought in with the skeleton: jeans, a camouflage shirt and a gray t-shirt reading ‘authentic urban quality” and sleeves knotted together. There’s also a gray messenger bag with white and black stenciled designs and a red bottom.

Photographs of the distinctive t-shirt and bag will be part of this John Doe’s NamUs profile, photographs that hopefully a friend or family member will recognize because Anderson doesn’t expect to make a match for this case with medical records. The office has used medical records, especially dental records, for identifications before but usually those matches come from people who’ve had dental treatment in the United States.

“There’s no way he had ever saw a dentist – he has crooked teeth and never had orthodontia,” Anderson says.

Based on where he was found in Pima County, Anderson suspects this man crossed the border from Sonora into Arizona somewhere between Sasabe and Altar or between Sasabe and Lukeville.

The skeleton was incomplete because some limbs were removed from the body and the area, probably by animals, yet there’s also some extra animal bones included in the bag. Those will be removed and disposed of separately.

“In addition to recovering the human bones whoever did it picked up some vertebrae of an animal or whatever it is,” Anderson says. “That’s usually a good sign that the recovery was thorough, that they just picked up everything.”

Now that the bones have been cleaned and analyzed the last step is to take a bone sample for DNA that can be compared to law enforcement databases, family samples and previous PCOME cases.

The lab also keeps DNA reference samples from PCOME staff.

“I’ve been looking at this case for a week now,” Anderson says. “Undoubtedly my hair is on the skeleton and if they were to swab the surface of the bone, more than likely, my DNA profile would come up.”

For sample cutting, Anderson prefers a standard Stryker saw to disposable carbide blades. He cleans the saw blade with bleach before and after every sample.

If it’s available, Anderson prefers to cut a sample from an upper thighbone or femur.

“That will give us a thick piece of cortex and the DNA labs like that,” Anderson says.

The blade spins into life and Anderson leans over the table. Its screech sounds – and soon smells – like getting a filling at the dentist, hot and funny like hair in a candle. There’s a soft spray of something as the saw moves across the bone.

Anderson sets the sample on the table and goes to change his gloves before he picks it up again.

Anderson holds out the sample. It’s about the size of three large dice if they were glued together except that the bone is curved with a darker, softer looking layer in the bottom of the ‘U.’

He wraps the bone sample in a circle of sterile culture paper and slides it into a manilla envelope. On the outside he writes in black permanent marker: the ML case number, R femoral sample, approx 13 g, the dates and his initials, BEA.

“The DNA lab needs about 1 gram although they have got DNA profiles out of less than 1 gram,” Anderson says. “We try to give them a minimum of 5 grams. A bone sample this big, roughly the size of a pair of dice is going to weigh about 20 grams more or less.”

He seals the package with tape.

“And mind you, we don’t lick the envelope.”

Now it’s time to remove a tooth for the secondary sample.

“Sometimes we have a concern: what if we have the wrong head for another body,” Anderson says. “We don’t have that concern here, but sometimes the bone doesn’t yield a DNA and then the teeth almost always will.”

Extracting DNA from teeth takes longer than working with bone but a tooth sample provides BODE with a plan B if anything doesn’t work out with the bone sample.

“So we are going to take tooth number-2, you can notice a complex root here,” Anderson says. “You can probably just wiggle that out.”

Anderson works with his gloved fingers for a few minutes but the tooth, the second molar, doesn’t want to be released.

“Okay, I’m going to need some help,” Anderson says, reaching for a pair of small pliers. “We have one thing special about him that the family may know about him and we’ll talk about that in a minute.”

He gently braces the skull upside down on a small ring of foam, grips the tooth with the pliers and begins to apply torque. It loosens gradually than seems to release suddenly.

“The DNA, if there’s any in a tooth it’s going to be in the pulp, the dent surrounding the pulp chamber,” Anderson says. “This happened before where we actually found intact blood cells in the pulp chamber. But the protocol usually is to try to crack the tooth open and then get DNA out of the dent. A dent is a lot like bone, it’s the yellow part of the tooth, not the white crown.”

The tooth, which weighs approximately three grams, is wrapped in sterile culture paper, is slid into an envelope, labeled “tooth 2” and taped like the bone sample before it. Then each sealed envelope is slid into a plastic sleeve and sealed again.

“We’ve been sampling bones this way and packaging it this way with these little coined envelopes for fifteen or sixteen years,” Anderson says. “BODE knows what to expect – and we kind of do it the same way every time.”

Now this sample package will wait. If there’s a break in the case, a possible specific match, this sample will jump to the front of the que.

“Let’s say we publicize that shirt on NamUs next week or next month and then we get a call,” Anderson says.

The caller could be a family member, law enforcement, a consulate case worker or occasionally an amateur detective browsing NamUs.

“If he was this tall and this age and wasn’t missing any upper teeth, we say check, check and check,” Anderson says. “It could be that he’s missing in Christmas time 2014 or 15 and yeah – that could be him.”

If the cases are close enough for a circumstantial match, the sample will jump to the front of the que for DNA testing. Law enforcement, consulates and outreach groups like Colibri, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) all help collect family reference samples. Sometimes they also help families cover the costs.

“We eventually get the samples back,” Anderson says. “We have hundreds.”

If there’s no circumstantial match, the sample will wait with others until another round of grant funding comes through.

Either way, the DNA profiles are kept on file. They include what’s submitted as match possibilities by the family, law enforcement and any other sources including earlier PCOME cases.

“This guy’s mandible or upper arms might show up,’ Anderson says. “We want BODE to be able to say, ‘Hey, those two cases, the 2014 case and the 2016 case, that’s actually the same person,’ and those scenarios happen on a regular basis.”

There’s one more thing that Anderson notes about this John Doe.

He picks up the skull and turns it to face right.

“We have this body protuberance called styloid process and they grow off our temporal bone,” Anderson says. “It’s on the count of thirty millimeters.”

He’s pointing at a spur of bone that juts out from behind the jaw into space that used to be filled with ligaments and muscles.

“He has what’s called Eagle syndrome,” Anderson says. “People afflicted with this, they’re at a risk for losing consciousness if they turn their head too quickly.”

Anderson says it’s unlikely that the condition was formally diagnosed, but when narrowing down potential matches Colibri staff can ask the family about symptoms: did he have dizzy spells or complain of neck pain?

“This is different,” Anderson says. “And we’d like to say here that anything different here is good.”

Something different could be the lead that generates an identification for someone when there are so many cases to work.

“My job is to try to find A an accurate description and B anything that sets him apart, something unique,” Anderson says. “And this is as close to unique that I can see on this table right now – it might help, it might not. ”

But at the end of the day, Anderson suspects that the key to a potential identification match for this John Doe will be his personal t-shirt or his recognizable backpack and, finally, a DNA test.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!