Lonnie David Franklin Jr. (also known as the Grim Sleeper) is the longest-operating serial killer west of the Mississippi with over 80 victims. For years, he eluded authorities, until his son was arrested in 2009 and detectives found a partial match to DNA found at the Grim Sleeper crime scenes. Using familial DNA searching techniques (FDS), detectives were able to identify and arrest Franklin.

In a 2016 interview with ISHI, Rockne Harmon described FDS as “an additional search of a DNA profile in a law enforcement DNA database that is conducted after a routine search fails to identify any profile matches. The FDS process attempts to provide investigative leads to agencies engaged in the pursuit of justice by identifying a close biological relative of the source of the unknown forensic profile obtained from crime scene evidence. FDS is based on the concept that first‐order relatives, such as a sibling or parent/offspring, often will have more alleles of their DNA profiles in common than those of unrelated individuals.”

Written by: Tara Luther, Promega

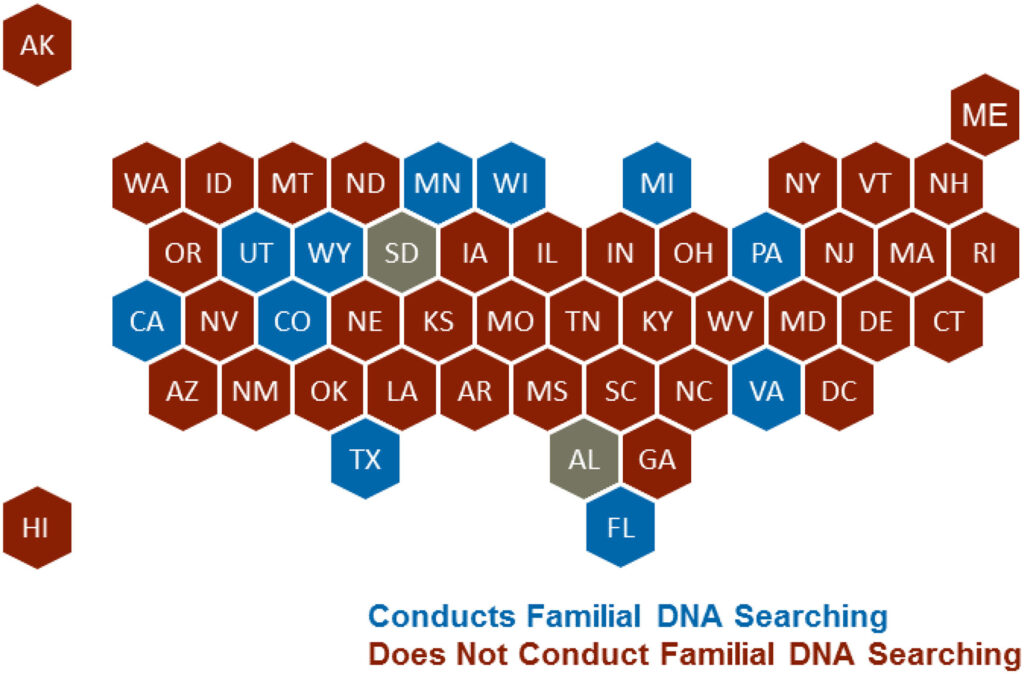

Since 2010, FDS has continued to close cases, such as the murder of Karen Klass, ex-wife of Righteous Brother’s singer Bill Medley. To date, only 12 labs in 11 states report using the technique. Advocates such as Rockne Harmon say that a wider implementation of FDS could solve tens of thousands of cases in the US, but critics express privacy concerns.

To date, little empirical research exists showing the policies and practices of labs regarding FDS, how the justice system operates in conjunction with FDS cases, or to showcase the outcomes of FDS cases. Looking to fill that gap, Sara Debus-Sherrill and Michael Field of ICF conducted a national survey of labs to get a better understanding of how FDS is being used and the perceptions around it.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, and included these topics: lab/respondent background, legislation and policies, scope of using FDS, perceptions and opinions of FDS (including benefits and concerns), and specific practices related to FDS (e.g., eligibility criteria, lineage testing protocols). In total, 103 crime labs representing 48 states, Washington D.C., one U.S. territory, and two federal labs completed the survey.

The survey began by asking whether or not the respondent’s lab utilized FDS. Of those surveyed, 12 labs in 11 states reported conducting FDS, with the earliest lab beginning in 2007. Of the labs who do not currently conduct FDS, 42% say they are considering using it in the future, and 75% have discussed using the technique in the past.

When asked why they didn’t currently use FDS, labs listed the following: a lack of clear guidelines, expected usefulness, training, technological considerations, cost/resources, civil liberty concerns, and whether or not the technique was prohibited by their state or another entity.

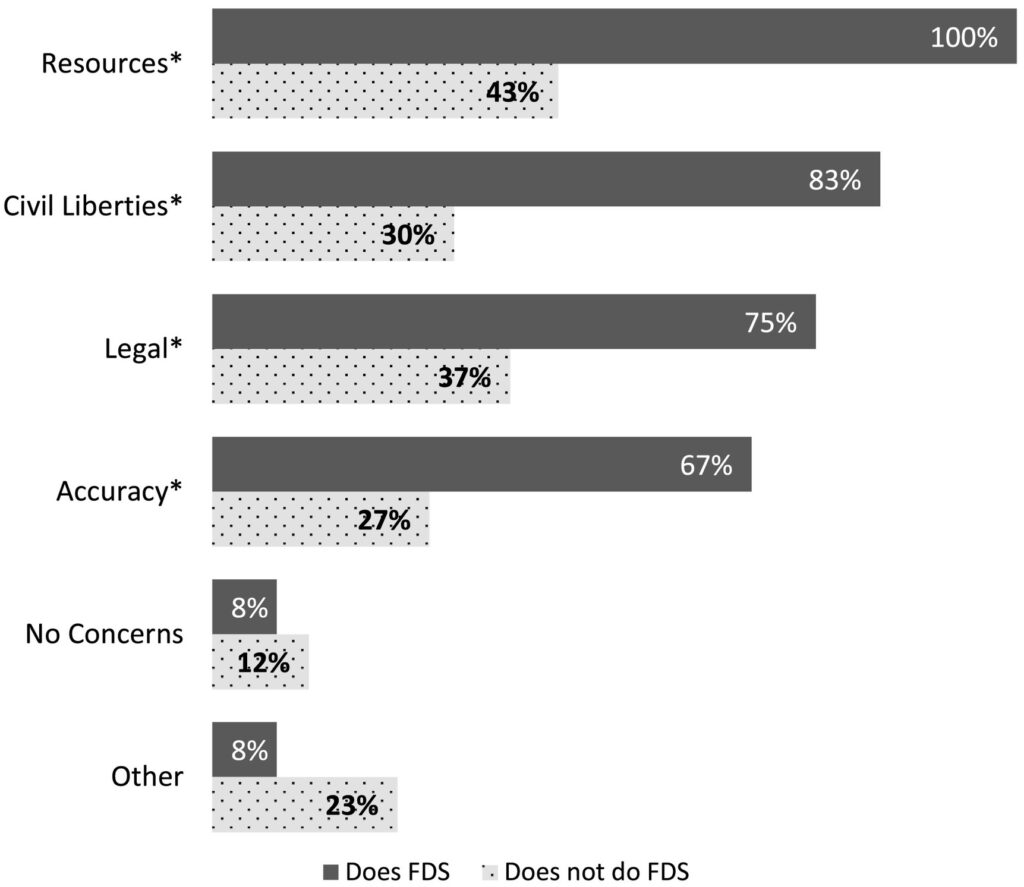

Addressing concerns by critics, such as privacy rights being potentially violated, the survey then asked respondents if they had any concerns with using FDS. Aside from privacy concerns, the survey also addressed potential resource constraints (staffing and funding, legal concerns such as the case being overturned, and accuracy (false positives). As the figure below shows, respondents marked their top three concerns as resources, civil liberties, and legal. Interestingly, labs who are currently using FDS expressed significantly more concerns than those who did not. Debus-Sherrill and Field noted that this could be due to FDS labs having thoroughly discussed the topic prior to implementation.

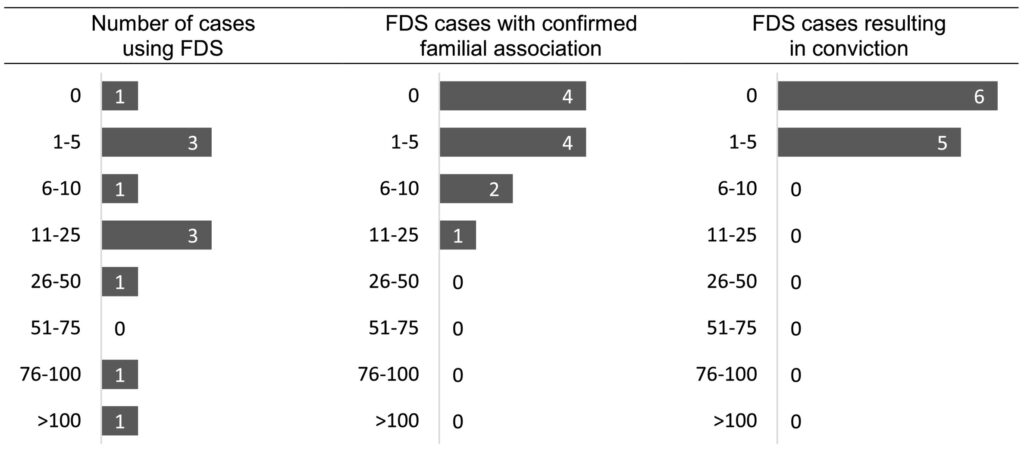

The survey then asked further questions of those labs that currently use the FDS technique. First, respondents were asked to share the total number of FDS cases performed, as well as the number of cases that resulted in a confirmed familial association and the number of cases resulting in conviction. The results show that while the number of total familial searches varies greatly, the number of convictions from FDS cases is low across all labs. In fact, only five labs reported having any cases that resulted in a conviction.

Next, respondents were asked to list which criteria needed to be met in order for them to perform a FDS. Labs tended to have consistent practices for utilizing FDS, such as exhausting all other investigative leads, DNA sample specifications (number of profiled alleles or being single-source), commitment from police or prosecution to pursue the case, a high public safety risk, and only accepting particular crime types (typically violent crimes). The majority of labs accepted both active/open cases and cold cases.

Labs were also asked which entities in their jurisdiction typically request or approve familial searches, since FDS doesn’t occur as part of a routine CODIS search. Of those who responded, 73% reported the requests coming from police agencies, 46% reported requests coming from the lab itself, 27% from the prosecution, and 18% of reported requests coming from a multi-stakeholder committee. All labs agreed that the crime laboratory must approve the request, and some labs required additional approval from a multi-stakeholder committee, police, or the prosecution. When disclosing the identity of a DNA profile found through FDS to law enforcement, all labs performing FDS declared they must conduct Y-STR testing on potential male relatives, confirming lineage testing’s key role in FDS.

Next, respondents were asked about any differences that existed in investigative processes when using FDS. 75% of labs reported that extra considerations needed to be taken to ensure privacy of potential relatives of the offender, additional education was provided to law enforcement on the search results and the construction of a family tree, and that FDS cases were assigned to detectives with special training.

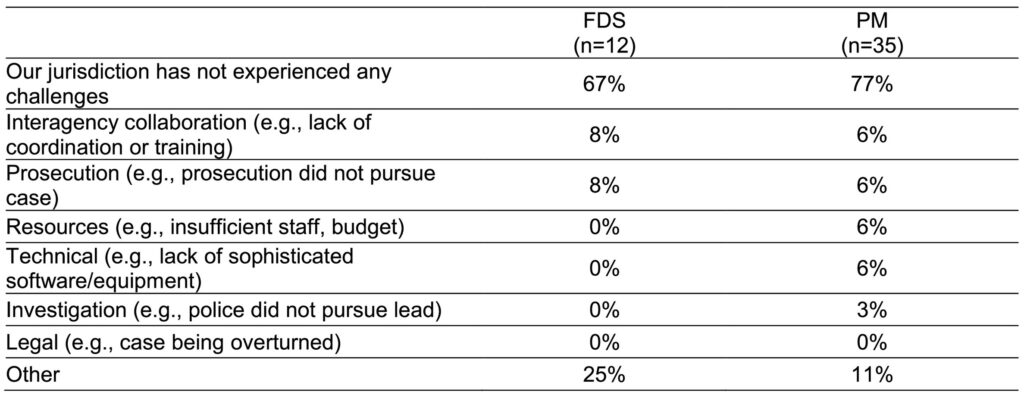

At the conclusion of the survey, the respondents who performed FDS were asked to report on the challenges they experience. Only 33% of labs reported that they experienced challenges when using the technique. In addition, none of the labs reported any legal challenges against FDS in courts in their jurisdictions.

Overall, Debus-Sherrill and Field found the perception of FDS to be generally positive with 87% believing the technique has the ability to assist investigations, yet there are still concerns that exist, with the main objection being a lack of guidelines or logistical concerns. If you work in a lab, do you agree with these survey results? Are you currently using or looking to implement FDS? Join in the conversation on our social media pages!

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!