CeCe Moore helped create the genetic genealogy team at Parabon Nanolabs and has been involved in 69 cases over the course of 17 months at Parabon. She’s also something of a celebrity in forensic circles, with many television appearances and articles published in the news media. There’s one case, however, that stands out for her. At the 30th International Symposium on Human Identification (ISHI 30) in September 2019, Moore discussed “Unraveling the Twisted Case of Angie Dodge.”

Written by: Ken Doyle, Promega

Written by: Ken Doyle, Promega

On June 13, 1996, the body of 18-year-old Angie Dodge was found at her apartment in Idaho Falls, Idaho. She had been raped and brutally murdered early that morning. Part of the evidence collected at the crime scene included semen and hairs from the same suspect, based on the DNA testing available at the time. The following January, police arrested Christopher Tapp, a 20-year-old man living in Idaho Falls, despite the lack of a match between his DNA and that obtained from the crime scene samples. The police were working on the theory that multiple people were involved in the rape and murder.

After extensive interrogation, Tapp confessed to the crime. None of the information he provided led to the successful identification of the other suspects. Tapp later maintained that his confession was coerced and appealed the conviction, but it was upheld in 2001 by the Idaho Supreme Court. His subsequent petitions were also unsuccessful. It wasn’t until a combined effort by the nonprofit organizations Judges for Justice and the Idaho Innocence Project that Tapp’s rape conviction was vacated in 2017, his murder sentence was reduced to time served, and he was released. (For more about The Innocence Project, see Presumed Guilty: Exonerating the Wrongfully Convicted in the July 2019 issue of The ISHI Report.)

One of the most powerful voices ultimately proclaiming Tapp’s innocence was an unlikely one: Carol Dodge, Angie’s mother. She had watched the tapes of Tapps’s confession in 2017 and had concluded that the confession was coerced. “Instead of wanting the death penalty for him, which is what she originally wanted,” Moore recalls, “she started fighting to get him out of prison.”

All the while, the search for a match to the DNA samples from 1996 continued. The complexity of the case led investigators down several false trails. One of those trails took them to the home of an amateur filmmaker in New Orleans named Michael Usry. In 2014, investigators used the technique of forensic genetic genealogy (FGG) to compare the DNA profile obtained from the evidence samples to those in a genealogical database originally developed by the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation and later acquired by Ancestry.com, a consumer DNA testing company. Using Y-chromosome analysis, which traces male lineage, they found a partial match between the unknown DNA sample and that of a man in the Usry family tree. This match, along with Usry’s 1996 trip to Idaho and the violent nature of one of his films, convinced police they had found their man.

“This was just based on his Y chromosome match alone,” Moore says. “It turned out when they tested his autosomal DNA, he was not a match to the genetic profile. Unfortunately, this ended up causing lots of negative media for genetic genealogy and also for ancestry.com.” As a result, Ancestry.com took the Sorenson database offline, and the genealogical community lost a valuable resource. Usry was released in 2015.

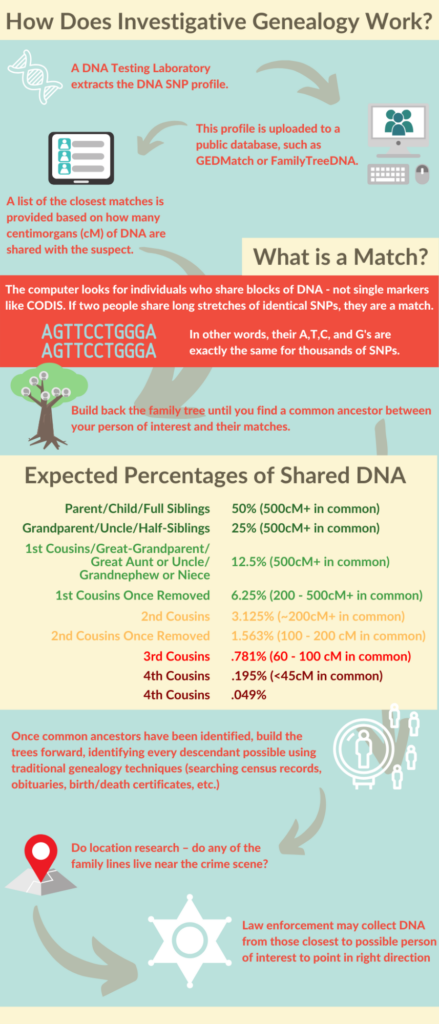

In May 2018, the IFPD gave Parabon permission to try another variation of FGG, using a publicly accessible database called GEDmatch. Unlike the Y-STR analysis that had led them erroneously to Michael Usry, the new analysis would use autosomal DNA typing to examine over 600–700,000 SNPs across the genome, providing a far more comprehensive genetic profile of the suspect. The DNA profile would then be compared to those available in GEDmatch, using traditional genealogical methods to find a match to relatives of the suspect. FGG had recently gained widespread media attention, after it resulted in the arrest of Joseph DeAngelo in the Golden State Killer case by a team led by Paul Holes and Barbara-Rae Venter—finally putting to a rest a case that had consumed much of Holes’ career.

There was only one problem with the DNA sample from the Angie Dodge crime scene: it was heavily degraded. “We only had a 61.2% call rate,” Moore recalls, “so we were missing about 329,000 SNPs from the 850,000 that we test.” Typically, genetic genealogy testing uses fresh samples, such as cheek swabs or saliva, submitted by consumers wishing to learn more about their family ancestry.

“I originally passed on doing genetic genealogy because of the results and the low call rate,” Moore says. A few months later, she was contacted by Carol Dodge, who begged Moore to go ahead with the FGG analysis. Despite serious doubts about the technique’s viability, Moore returned to the DNA profile. “If a profile is not viable for genetic genealogy, then it just will lead us in circles,” she explains. “It’s not that we will identify the wrong person, we just won’t find any patterns.”

Despite her reservations, Moore obtained permission from the IFPD to proceed with FGG that fall and started her in-depth genealogy research. In early 2019, Moore delivered her report to the IFPD. After making some adjustments to the technique to account for the degraded sample, to Moore’s surprise, the top four matches on her list shared 85–95 centiMorgans (cM) of DNA with the suspect. Although there are multiple relationship possibilities within that range—for example, second cousins once removed, a half second cousin or even a half first cousin—Moore considered the results promising, despite the quality of the DNA sample. She ended up building three different genetic networks and trying to determine where they converged on an ancestral couple from which the suspect was likely to have descended. Initially, Moore’s analysis pointed to an ancestral couple named Joseph Lathrom and Orlena Gaither. However, another network revealed a name that sounded familiar to Moore—Martin Ussery.

“If you’ve been doing genealogy for a while, you know names change. There’s a lot of variants in surnames, and so when I saw this, I realized the Y chromosome analysis was correct. The suspect very likely was carrying a Y chromosome from an Usry family.” In this case, Moore used what she calls “reverse genealogy”—building a family tree forward in time, rather than backward. Combing the two genetic networks, she concluded that the suspect would have to descend from both ancestral couples, with the Usry/Ussery family determining the paternal lineage of the suspect as shown in the Y-STR analysis.

In the end, Moore’s exhaustive analysis that combined genetic genealogy with traditional genealogical records (like newspaper archives, public family trees, obituaries and other public records) resulted in a list of six possible leads for the IFPD. The most likely suspect lived in Twin Falls, Idaho, and so the IFPD attempted to obtain a DNA sample surreptitiously from items discarded by the person being tailed—cigarette butts, tissues, water bottles, or anything else that could contain DNA. Eventually, they succeeded in retrieving a wad of chewing tobacco and sent it for DNA analysis, but the profile was not a match to the one from the crime scene.

Despite the negative result, Moore considered the analysis useful, because it could help to eliminate or include that particular branch of the family tree. Further analysis provided more disappointment, as the relationship between the person in Twin Falls and the DNA profile proved to be more distant than originally thought. In other words, it was extremely unlikely that the remaining five leads would prove to be fruitful.

“It was incredibly discouraging, because I’d never had a case where it wasn’t one of the descendants that I had found beneath that triangulation [of genetic networks],” Moore says.

Yet, spurred on by Carol Dodge’s pleas, Moore resolved to continue investigating. She recommended uploading the crime scene DNA profile to a different genealogy database, FamilyTree.com, hoping to clarify the matches obtained earlier from GEDmatch. A distant match intrigued her—a man who was a descendant of all three identified genetic networks. Yet, he had no apparent connections to Idaho and no criminal record. A search of the records at a small library revealed an obituary for a woman whose daughter had married into the family tree identified by the previous analysis. However, that marriage had ended before producing any children, causing Moore to eliminate this branch of the tree earlier.

The obituary that Moore uncovered also listed a son named Brian Dripps. “Now we have Brian Dripps, who descends from all three of these genetic networks, but he’s got the wrong last name,” she says. “He’s got that Y chromosome from the Usry family…but he’s not carrying that surname.”

As it turned out, the Dripps name belonged to Brian’s stepfather, who had raised him. Moore was determined to find out anything she could about this seventh lead. She discovered that Dripps lived in Idaho Falls in 1996, the year Angie Dodge had been killed. Acting on Moore’s new report, IFPD detectives found old records and receipts showing that Dripps had been living directly across the street from Angie Dodge at the time of the murder. Dripps also resembled the genetic phenotyping profile that Parabon had generated several years earlier after adjustments for his current age.

One final step remained: to find Brian Dripps. The investigative team tracked him to Caldwell, Idaho and after a couple of unsuccessful attempts—including detectives risking their lives in traffic to retrieve evidence—they recovered a cigarette butt discarded by Dripps. DNA analysis provided a positive match to the sample obtained from the crime scene, nearly 23 years earlier.

Still more twists and turns followed, as detailed in the police report, before the police finally arrested Dripps on May 15, 2019. He later confessed to the crime and stated he had acted alone.

“Now we’re working many cases with degraded DNA. We have a successful identification down to a 58.8% call rate, so it’s much more viable than I would have imagined,” Moore says. Technological successes aside, she highlighted what really mattered in the case. “Identifying Angie’s murderer for her mother Carol…was so fulfilling and so huge, but also helping to clear the name of an innocent man made it just that much better.”

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!